"The world already has enough straight lines. And too few dinosaurs." - Andy White

~

DINOSAURS, RABBITS, DRAGONFLYS – oh my! Hailing from Michigan, anthropologist and archaeologist Andrew A. White, Ph.D., moved with his family to Columbia last July, in the middle of a sweltering Southern summer. White holds the position of Research Assistant Professor with the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of South Carolina. However, in his spare time, he creates animal sculptures out of scrap metal and found objects. With a background in welding, White uses his metalworking skills to construct artistic renditions of various species in the animal kingdom.

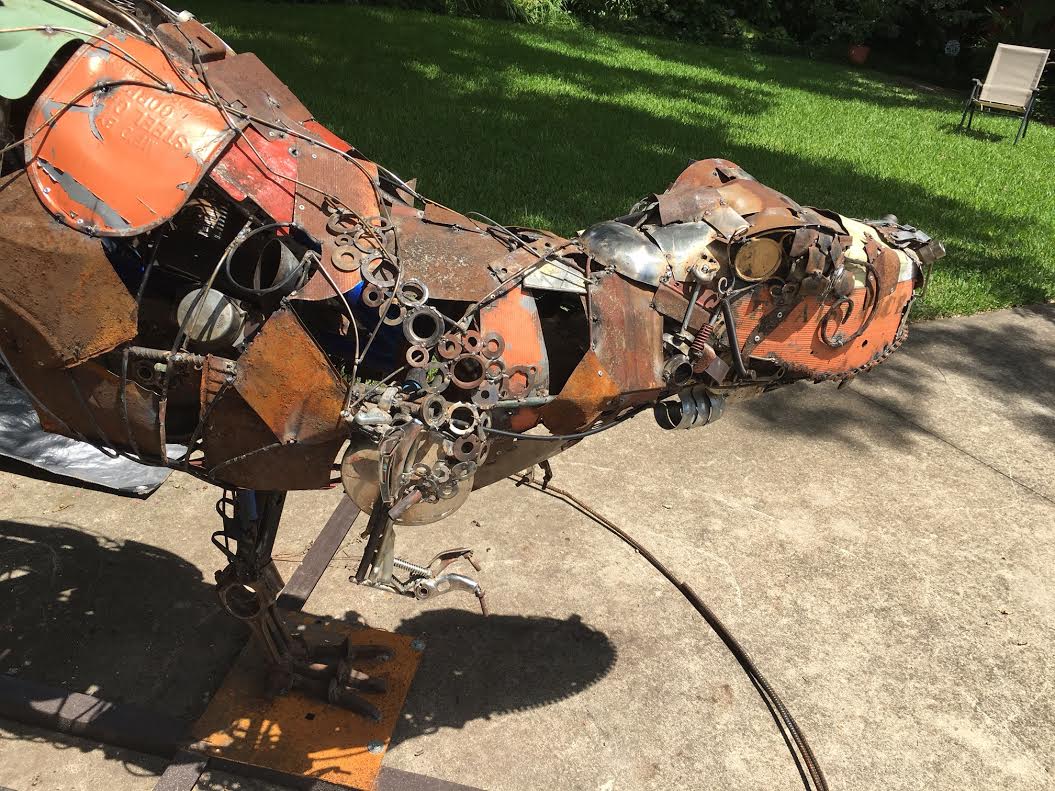

Working out of his garage, Andy White has built a sundry of creatures, including a Tyrannosaurus rex, triceratops, rabbit, snail, dragonfly, and crow. While each sculpture currently remains in his yard, the broad-based appeal of these whimsical yet sturdy designs cannot be ignored. The detail and craftsmanship in his work is readily apparent.

From afar, the pieces sit like industrialized replicas of magnificent creatures, some with outsized proportions that make them all the more striking. Upon closer inspection, the time and consideration taken by White in piecing together the anatomies and choosing relevant parts quickly emerges – household objects ranging from silver spoons to frying pans decorate the sides of various animals.

It seems natural for White’s artwork to occupy public or private spaces of various sorts. Displaying his sculptures would serve as a welcome addition to the art scene in Columbia, livening up our city with a recycled art form that is both refreshing and memorable.

Andy White kindly agreed to answer the following interview questions. His responses will hopefully spark the Columbia community to learn more about this scientist and artist. Thanks Andy!

~~~~~

When did you first start making sculptures?

White: I’ve been trying to make things for as long as I can remember, so it’s not really a question of “when” but a question of changes in “how” and “what.” I started welding in 2010. Learning how to weld steel made it possible for me to assemble larger and heavier things than I ever could before, allowing me [to] make bigger sculptures that could survive outside. Before I began to weld I worked with sheet metal on and off for years as best I could, using bolts and screws to build three-dimensional pieces and using tacks to make two-dimensional designs attached to wood. The ability to weld removes a lot of constraints on what you can and can’t physically make with metal. Aspects of my personal and professional life kept me from welding during most of the last few years, but I’m happy that I’ve got the space and the time to do it again now.

What inspires the subject matter for your sculptures?

I like making animals because of their curves. Not only do I think that curvy things are more interesting to look at (I like Art Nouveau much more than Art Deco), but building something curvy makes it much less problematic that I’m a sloppy artist and a terrible welder. While I admire people who are very good technical welders, I don’t want to have to sweat the details of straight lines. The world already has enough straight lines. And too few dinosaurs.

A lot of the pieces of metal that I use have personal associations with certain times or places. I like putting those things into a sculpture because it creates a kind of scrapbook – those bits and pieces hold memories, and creating something new with them gives those memories a physical place in the present. I’ve found that blending memories together makes some of them blurry, but I think that’s okay too. Ferrous metal will rust away into nothing eventually, just like memories do. You have to make conscious decisions sometimes how much effort you’re going to put into preserving relics of your own past. What do you hold on to and what do you let degrade into nothing? My sculptures provide a way for me to work through that.

Can you please describe your artistic process, if any, for creating your pieces?

It usually starts in my head with an idea for something I want to build rather than holding a piece of scrap in my hand and saying “this could be an eyeball” or something like that. I will generally browse pictures of living animals online or in books and see if I can find a posture that I like for whatever creature I’m thinking about. Sometimes I’ll print out an image and take a few measurements to guide scaling the anatomical proportions somewhat accurately. But often I’ll just keep eyeballing the piece as I go, adding things for strength, volume, shape, etc., and trying to get the key attributes I’m looking for to “click.” Sometimes I’ll have a piece of metal that I really want to use because I like the way it looks or because it has a strong memory attached to it, but I won’t be able to find a place for it. Sometimes I get “stuck” because I don’t have things around that will make what I’m building look like what’s in my head. Sometimes I find something new on the street and it takes the piece in a different direction. Sometimes a change of direction is probably for the better, and sometimes it’s probably not, and usually there’s no way to know because you have to choose a path and go with it. Sometimes I’m in love with what I’m doing, and sometimes I hate the damn thing. Sometimes I burn myself or cut myself, or something falls off the sculpture or the crane falls over on me. Eventually I become more interested in working on something else, and whatever is inside the garage gets put outside. That’s how I know it’s done.

Why did you choose to pursue Anthropology and Archeology as your profession?

Humans and human societies are the most difficult things in the world to study and understand. We are part nature, part culture, partly the products of our environments, and partly bound to history. And while studying human societies in the present is difficult, studying them in the past is even harder. Archaeologists have to find ways to make credible statements about the past based on a pretty sparse jumble of material evidence that is intentionally or unintentionally left behind. We can’t directly observe the societies we want to study, but have to look for patterns in those few material traces that remain. We have to not only compel those things to tell stories, but we have to find ways to test those stories and see if they make sense. The science of the human past may be the most challenging kind of science one can choose to do. But that also makes it the most fun.

How does your background in Anthropology/Archeology influence your metalworking?

Indirectly, I think, in a couple of ways.

First, the material evidence that archaeologists work with is largely the debris of everyday life– stuff that’s been discarded, lost, left behind. Sometimes the things that end up in the archaeological record have symbolic meanings attached to them, but often they don’t. Sometimes things that are thrown away lose their original meanings but are later used by someone else who may attach new meanings. That’s sort of what I do as well, creating objects with new meanings from collections of cast-offs.

Second, three-dimensional things require a structure that provides both strength and form. There are different strategies for doing that in the natural world (you can have your skeleton on the inside, like mammals, for example, or on the outside, like insects and crustaceans). Each has its advantages and disadvantages. There are different strategies for organizing human societies, also, that are associated with different strengths and vulnerabilities. When you build something artificial, you have to think about the sources of strength and form. Does the strength come from some kind of robust central frame, or from the interconnectedness of numerous smaller parts? Do the same structures provide both strength and form? Building three-dimensional objects out of scrap metal presents logistical and artistic challenges, the “solutions” to which can have parallels in both natural and cultural phenomena.

Do you have any future projects in store? Would you ever be interested in making public art?

I always have something in the works . . . sometimes I sweep the garage floor between projects, and sometimes not.

Everything I’ve done so far has been (mostly, anyway) for me. I make what I want when I have time to do it. I enjoy the process and the results, and those things together make it rewarding. Purposefully making something to be displayed in public would change that equation somewhat, but it would be fun to give it a shot if it was an interesting idea that I thought I could pull off and the product would be somewhere I could take my kids to see it. I would have to make some adjustments to produce a piece suitable for a public, outdoor space: it would have to be less ornate and I’d have to pay closer attention to leaving sharp edges.

What's one of the most bizarre items you have found on the streets? Have you ever encountered any problems picking up debris from the curb?

I’ve found much stranger things doing archaeological fieldwork than I have cruising the curbs. I cannot mention those things.

Did you ever expect to garner publicity surrounding your at-home art projects?

No! They’re in the back yard for a reason! It’s flattering when people have nice things to say, but I’d do it regardless. As long as my family likes them well enough that I can keep some in the yard, I’m good.

Just for fun: If you could time travel, what time period would you go to?

I think I’d probably go back to the Middle Paleolithic, around 200,000 years ago. Despite all the human fossils and archaeological sites that we know of from this time period, there remain intense debates about what humans and human culture were like then. Although it’s a poorly understood time period that I would like to visit, however, I think I know enough about it to know I wouldn’t want to stay for long.