There was a moment during a dress rehearsal of Collected Stories earlier this week that simply crushed me. The stage was dark, and a stagehand went around the set in the darkness, slowly and methodically making a mess of the place. A plant toppled, papers strewn across furniture and floor, prescription bottles scattered on desk and table, a curtain undone, a shawl tossed in the floor.

There was a moment during a dress rehearsal of Collected Stories earlier this week that simply crushed me. The stage was dark, and a stagehand went around the set in the darkness, slowly and methodically making a mess of the place. A plant toppled, papers strewn across furniture and floor, prescription bottles scattered on desk and table, a curtain undone, a shawl tossed in the floor.

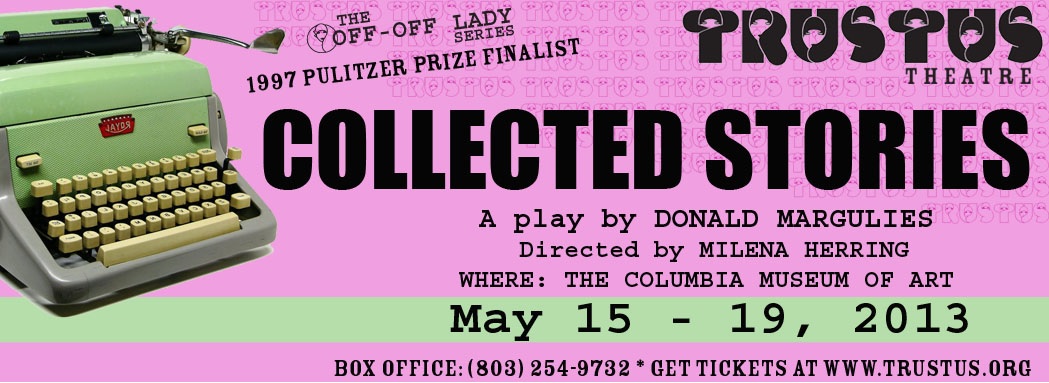

Collected Stories, a play by Donald Margulies, opens at Trustus Theatre this Thursday, August 15, and closes on Sunday August 18. It’s a short run for a powerful little play, directed by Milena Herring. In a sequence of short scenes over the course of six years, we see Ruth Steiner, an older writer and teacher, take on as her student and later assistant the seemingly innocent Lisa Morrison, a 26-year-old would-be writer. I say seemingly innocent, as it’s never clear how manipulative and shrewd she really is. As the balance of power between the two shifts, we wonder at the end who the real innocent might be.

Ruth is played by the indomitable Elena Martinez-Vidal, confident and pitch-perfect throughout the play. A couple of moments feel performed for the audience as much as they are for Lisa—stagey, theatrical, but that feels right. Ruth’s little Greenwich Village apartment is her stage, Lisa her pupil and audience, and she is acting out what a famous writer is and says. I’m reminded of that scene in Douglas Sirk’s 1959 Imitation of Life, when Susie (Sandra Dee) tells her mother Lara (Lana Turner), “Oh stop acting mother!” But she can’t: she is always onstage. Martinez-Vidal is fascinating in this part, especially near the end, when Ruth’s life and health are ruined, and still some dark vitality—and anger—drives her speech and action. She bristles stiffly in what seems to be a conciliatory hug from Lisa.

Elisabeth Gray Engle as Lisa was a puzzle, a chameleon. Ingénue or ingenious, devious or devoted, we’re never really sure, though Engle, like Lisa, slowly but surely finds her voice. The moment she tells Ruth about a story her father hated, something shifts in the play, and we start to realize that Lisa, as Engle deftly portrays her, has more to her than we imagined.

Either character could have been a type character if not a caricature—the old Jewish writer and professor, the gushing would-be writer—but both actresses brought a real depth to their portrayals. The room itself, the set, is almost a character as well. Early in the play, Lisa rhapsodizes on how wonderful it would be to live in a place like that, a place perfect for a writer. She reads the space through Ruth’s fiction, noting a Matisse from this story, the view of a playground from that one. So when the stagehand comes through knocking over a plant and strewing paper and pill bottles, we realize that something has gone deeply wrong.

Two primary issues drive the play. One is power. When Ruth and Lisa argue over the guilt of Woody Allen after his affair with his 19-year-old step-daughter, we can’t help but wonder about the balance of power in this relationship. Ruth admits her own affair with an older man, the poet Delmore Schwartz, but she also says that she has never written about the affair, even though it was the bright moment of her life. “Some things you don’t touch,” she says, a command this daughter-figure is, we know, bound to disobey.

The second issue is the ownership of stories—and in an indirect way, lives. Ruth admits to exaggerating elements of her own biography for political effect, and the two women agree that writers “rummage” through other people’s lives for stories. “We’re all rummagers. That’s what writers are.” When one accuses the other, “You’ve stolen my stories,” the glib reply—“They stopped being your stories when you told them to me”— amplifies rather than answers the ethical questions.

In 1993, American novelist David Leavitt was sued by English poet Stephen Spender, who accused him of using a section of his memoir World Within World as fodder for his novel, While England Sleeps, a fictional portrayal of someone very like Spender. I can’t help but think this literary larceny inflects Collected Stories, which premiered three years later in 1996. (Leavitt’s next published work was The Term Paper Artist, a wicked novella from the point of view of an author accused of plagiarism, who starts to write term papers for college students.)

Where does theft stop and imagination begin?

Even though Ruth may think she’s granting voice to the voiceless, or Lisa may claim she is paying homage, there’s still a real sense here of ethical risk, one that carries, for me, beyond the play. This would be a fascinating play to discuss in a creative writing class, where questions of writing about real people, people we know, inevitably lead to complex conversations. What happens when our families read themselves in our stories (no matter how fictionalized)? Or what happens when we alter details in a presumably nonfiction piece for aesthetic effect. Yeah, we all know art is the lie that tells the truth (pace Oscar Wilde and Julian Barnes), but playful paradoxes rub raw when real people feel wronged.

Collected Stories closes out Trustus Theatre’s 28th season, and runs Thursday thru Sunday, August 15-18 (with a matinee on Sunday). It’s a rich play—and as a meditation on plagiarism, intellectual property, and dishonesty, a great way to start the school year. See it while you can. Contact the box office at (803) 254-9732 for more information, or visit http://www.trustus.org .

~ Ed Madden