From my work as co-director of The Vagina Monologues to my time spent with fellow writers and artists, I’ve gotten into a lot of discussions about the arts, media, and representation. Many of these discussions follow the same patterns:

From my work as co-director of The Vagina Monologues to my time spent with fellow writers and artists, I’ve gotten into a lot of discussions about the arts, media, and representation. Many of these discussions follow the same patterns:

Art is meant to provoke thought and discussion. We can’t govern the imagination.

People just write what they know. He’s a white guy writing about his experiences—he’s not purposely excluding people of different colors/genders/etc.

Sure, all of these characters are based on stereotypes, but at least this film gets people talking about sexual violence/gender stereotypes/race/etc.

As a writer, I have to admit that there is something to be said for some of these arguments. Many of the characters I create are representations of the various facets of my own identity, and while I try to step out of the boxes of my experience and imagine someone else’s, doing so is often a perilous adventure. What if I misrepresent this community? Do I really have the right to write what I don’t know but have only imagined, researched, and tried my best to represent?

Yet, as an artist who is also an activist and a feminist, I think that questions of art and representation must be constantly considered and go beyond my individual experiences as an artist.

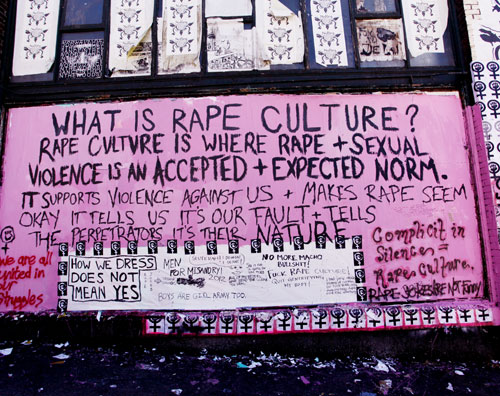

As the Prevention Education Coordinator at Sexual Trauma Services of the Midlands, I am invited into schools and community groups to teach our six-session Youth Violence Prevention Program. The first lesson that I facilitate is about gender stereotypes and the normalization of sexual harm. In that lesson, we look at the pervasive ways in which the media perpetuates gender stereotypes and also, in the end, promotes rape culture and makes sexual violence “normal.” Think of these Dolce and Gabbana and Calvin Klein ads, or this Rick Ross song, or any movie in which rape or abuse is eroticized (something that’s often hard to avoid on film).

One might try to argue that “The Arts” rise above this fray of marketing and populism. But it doesn’t, and I’m reminded time and time again that it doesn’t. From perpetuating the myth that “no really means yes” to supporting gender stereotypes (i.e., equating masculinity with violence/dominance or upholding the madonna/whore binary) to pigeonholing female characters/subjects as nothing more than romantic interests, “The Arts” are not immune to these issues of misrepresentation and the promotion of rape culture.

When I bring this up, though, my friends and colleagues often ask me, “Why throw the baby out with the bathwater? Isn’t it enough that this work has this great character of color/Trans* person/ Strong Female Character/etc.?” And my answer is that it’s not. Yes, art is art, art provokes, and I will not control another artist’s work. I may even praise artists’ use of X, Y, or Z, but that won’t stop me from challenging them to reconsider their (mis)representations of race, class, gender, etc. I won’t stand idly by while those works promote the rape culture I work to dismantle on a daily basis.

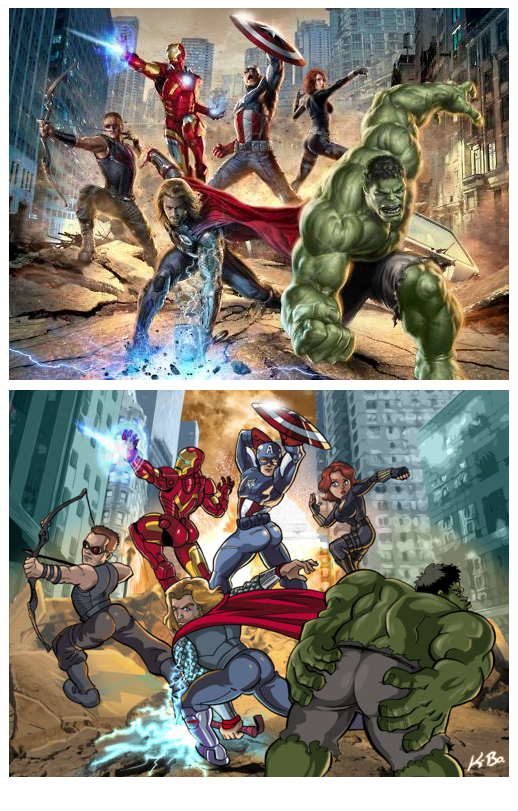

The film Miss Representation makes it clear that the socio-cultural and economic powers that be will make it difficult to create and distribute art/media that represents the voices of populations that are sidelined by those who dominate such industries. I cannot stop Robin Thicke from telling women what they want and objectifying the female body. I cannot get Adam Levine’s label to decry the intimate partner violence in the music video for “Misery.” I probably can’t even convince the beloved (and self-proclaimed feminist) Joss Whedon that just because The Avengers’ Black Widow is a Strong Female Character doesn’t mean she isn’t still overly sexualized. (Even for those who cheer on Whedon’s female characters, The Avengers still fails the infamous Bechdel Test.)

But as educators and artists, we have a choice. As an educator, I can teach others to be critical readers, viewers, and thinkers, celebrating the successes of art and media while also being willing to voice what is problematic about certain works. And I can encourage others to create works that speak out against privilege and that recognize both rape culture and inequalities that occur in the arts and media.

As an artist, I can create art that tells a different story—one that resists stereotypes, creates space for different voices, fights rape culture, and talks back to the racist, classist, sexist, ableist, heterosexist messages we receive day-in, day-out. I can create art that doesn’t think rape is a joke and perhaps instead calls out injustices and maybe even reflects the realities of the violence that many women face. I will make mistakes, but I can listen when those mistakes come to my attention. I can be self-reflexive, enter into conversation, and recognize where my own privilege creates blind spots.

In Miss Representation, Katie Couric says that the media (and I’ll add the arts to it, too) “can be an instrument of change: It can maintain the status quo and reflect the views of the society or it can, hopefully, awaken people and change minds. I think it depends on who’s piloting the plane.” I challenge you to pilot that plane, creating art that resists rape culture—and changing that culture in the process.

In Miss Representation, Katie Couric says that the media (and I’ll add the arts to it, too) “can be an instrument of change: It can maintain the status quo and reflect the views of the society or it can, hopefully, awaken people and change minds. I think it depends on who’s piloting the plane.” I challenge you to pilot that plane, creating art that resists rape culture—and changing that culture in the process.

Alexis Stratton is the Prevention Education Coordinator at Sexual Trauma Services of the Midlands, a Columbia-based organization that supports survivors of sexual violence and educates the community to identify and prevent sexual violence. As a graduate of the University of South Carolina’s MFA in Creative Writing Program and Women’s and Gender Studies Program, she has spent years working in the Columbia community (and beyond) to raise awareness about issues of gender-based violence and to empower community members to change the world around them.