BY OLIVIA MORRIS

Florence Foster Jenkins starts with a bird's eye view of 1944's New York City then cuts to an unconvincing monologist reciting Hamlet's long-butchered second soliloquy to a room filled with elderly couples in suits and derby hats. The curtains of the Verdi Club stage open to reveal a man dressed as Stephen Foster, "the father of American music", suffering from writer's block. Florence Foster Jenkins descends from the stage rafters, unevenly lowered by thick black cords, dressed as the Angel of Inspiration, complete with wings. She smiles and waves her hands around, until Foster suddenly pounds the famous notes of "Oh! Susanna." The brief scene closes without Jenkins having said a word. Off stage, she is dissatisfied with her performance, having not fully "embodied" her role.

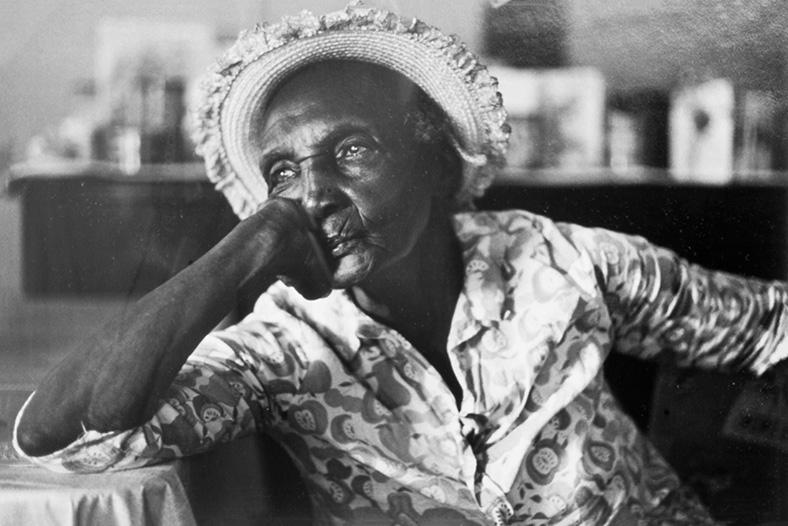

Florence Foster Jenkins is currently being shown at the Nickelodeon Theater, starring Meryl Streep and directed by Stephen Frears. The movie is based on the true story of its eponymous main character, an American socialite who showed great patronage to the early 20th century music scene. She is convinced of her singing ability, despite the fact that, as her pianist Cosme McMoon describes, "her vocal chords, they don't phonate freely. Her phrasing is haphazard. As for her subglottal pressure, it defies medical science." Her singing is encouraged by her second husband St. Clair Bayfield (Hugh Grant), the opening's mediocre Hamlet, who pays friends and reporters to praise the small concerts Jenkins performs. He hides negative reviews and is fiercely protective of Jenkins' feelings, but this task becomes overwhelming when Jenkins decides to give a public performance at Carnegie Hall.

Though the movie easily could have easily fallen down the slippery slope of slapstick comedy, it attempts a much more complex path. Jenkins is suffering from syphilis, which she contracted from her first husband on their wedding night. A combination of her illness, along with the arsenic and mercury she was using to treat it, likely affected both her hearing and ability to accurately evaluate her own voice.

This movie explores the idea of codependency — between people, lying and happiness, comedy and tragedy. The characters defy tropes, each one a combination of good, bad, and delusional. They are constantly redefining loyalty, questioning how much they owe to each other and how to display it. They also reshape notions of truth, questioning whether it is better to keep Jenkins happy and ignorant, or reveal the city's true perception of her. The movie makes you want to laugh at Jenkins, while simultaneously hating any character who does. It illustrates the irony of happiness and the wholesomeness of lying.

The movie is most notably a testament to human resilience. Jenkins has suffered through life childless, abstinent, and publically mocked. She is vain, placing one wig on top of the other instead of switching them out. She is self-righteous, commenting that she doesn't need a second take at the recording studio. However, she is also easily affected and open. She is shocked to hear sailors laughing at her performance in Carnegie Hall, one man even shouting "she sounds like a dying cat." However, the crowd is so impressed by her bravery and charm that they chant for her to continue singing until she belts out. The movie closes with Jenkins whispering to Bayfield, "people may say I can't sing, but no one can ever say I didn't sing."