One of the things that I have always loved about the film selections at Indie Grits is their desire to tell the stories about the South that have been pushed to the margins or swept under the rug, stories that can often feel jarring alongside the version of the region romanticized in Gone with the Wind or mocked in Bravo’s Southern Charm reality series. It’s a braver, weirder, and more exciting version of the South that Indie Grits is interested in, with a no-holds-barred examination of its past.

One of the things that I have always loved about the film selections at Indie Grits is their desire to tell the stories about the South that have been pushed to the margins or swept under the rug, stories that can often feel jarring alongside the version of the region romanticized in Gone with the Wind or mocked in Bravo’s Southern Charm reality series. It’s a braver, weirder, and more exciting version of the South that Indie Grits is interested in, with a no-holds-barred examination of its past.

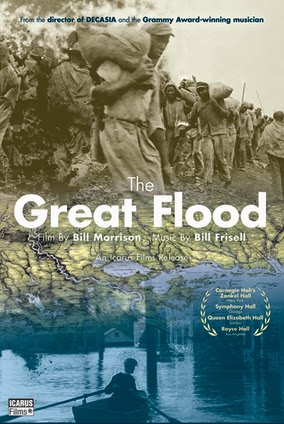

It’s fitting, then, that the first screening of the 2014 festival is of Bill Morrison’s The Great Flood, which looks at the devastating flooding of the Mississippi River over the course of the spring of 1927. It’s a beautiful and evocative film comprised almost exclusively of archival footage, much of which was pulled from the Fox Movietone collection housed at the University of South Carolina’s Moving Image Research Collections. Morrison manages to tell a painterly version of the disaster, with no voice over and spare use of placards, that subtly yet powerfully captures its social, political, and racial effects.

The film begins with a CGI version of the flood that interlaces recreated overhead shots and maps before cutting to the newsreels, where there are dedicated sections to sharecroppers, the 1927 Sears Roebuck catalog, levee construction, evacuations, politicians exploiting the tragedy, the unnecessary dynamiting of the levees in the Poydras area, the aftermath, and the migration of African-Americans into northern cities. While Morrison elegantly constructs a compelling narrative from his occasionally disparate material, it’s the extensiveness and poignancy of the footage itself that really inspires—the different approaches these cameramen take when documenting the sharecroppers (some of which was surprising humanizing, although other moments felt like outtakes from Birth of a Nation), the deteriorated film from long takes shot shot from rescue boats, the repeated looks of bewilderment from folks, black and white, who are losing everything and being filmed as it happens. Much of it has a surprising aesthetic beauty and humanity that recalls the work of the best photojournalists, although there's often a sense of distance and objectivity that can be equally heartbreaking. At times it is difficult to tell whether the original takes have been manipulated a bit, as the water can seem too slow or too fast to be real, and the quality of the footage varies from remarkably detailed to quite grainy. Regardless, the constant shifting of material keeps the audience on their toes and fully engaged.

The film also benefits in large part, given the lack of words and explicit narrative, from the arresting score composed by guitarist Bill Frisell, which was worked out over a series of rough cuts shown in advance by Morrison and ultimately recorded live at a screening in Seattle. Mostly featuring Frisell’s signature tone manipulations and the languid trumpet and cornet playing of Ron Miles, as well as Tony Scherr on bass and Kenny Wollesen pulling double-duty on drums and vibraphone, the quartet mainly focuses on capturing the haunting spirit of much of the footage, although they build to more distorted and fiery climaxes when the physical film itself begins to get too degraded or stark, and they also provide a couple of sprightly jazz during two appropriate sections (the jauntily cynical politicians section and the rapid-cut sequence on the Sears Roebuck catalog).

While the film’s experimental nature means it likely won’t be for everywhere, it’s hard not to think about the power it holds as historical documentation and social and political argument. Whether paired with the study of literature from that time period like William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms or William Alexander Percy’s autobiography Lanterns on the Levee, or with the modern-day explorations of Hurricane Katrina or the impacts of global warming, Morrison’s work deserves a wider audience and further interrogation. –Kyle Petersen