“Marley was dead to begin with…”

Charles Dickens – “A Christmas Carol”

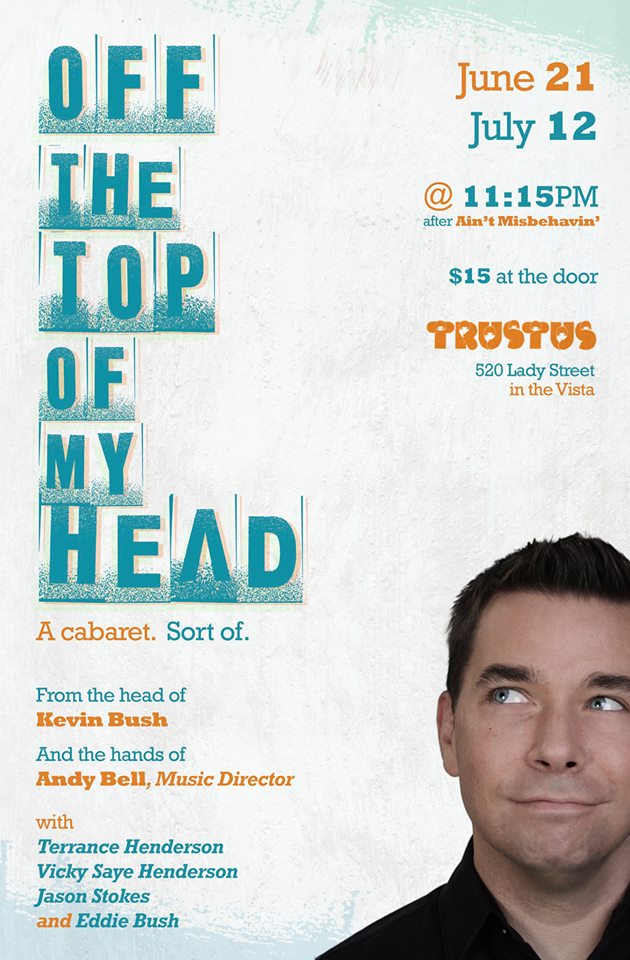

L to R — Richard Edward III, Kevin Bush, Krista Forster, Jeff Driggers

These six words are well-known by just about anyone who has ever read or seen a production of Dickens’ now-immortal (pun intended) holiday classic. The undeniability of Marley’s having left the realm of the living is also the first point established in Tom Mula’s Jacob Marley’s Christmas Carol, running through 22 December at Trustus Theatre. As a huge Dickens fan, as well as a Christmas nut, I eagerly anticipated seeing this production, and was not at all disappointed. Time, finances, and practicality usually prevent me from seeing local shows more than once, but I’m going to do my best to catch this gem again before it closes. Like its inspirational predecessor, this is a story with many layers and subtleties beneath the deceptively simple plot, and the combination of acting and directorial skill lives up to Trustus’ long-cemented reputation for professional and artfully crafted work. For those familiar with the BBC series, Dickensian, this script takes a similar approach to the world(s) created by Dickens well over a century ago, and turns perspective on its ear, giving us a glimpse of how certain events came to be, and an intriguing semi-prequel as seen from the viewpoint of a secondary character. (On a side note, if you haven’t seen Dickensian, look for it online. By coincidence, the plot centers around the murder of Jacob Marley, and characters from multiple Dickens novels are interwoven throughout.)

…but, I digress. I’m here to discuss what’s being presented onstage at Trustus, so let’s get to it. As Jacob Marley’s Christmas Carol opens, a recently-deceased Marley has arrived in a posthumous waiting room, where he encounters a sort of eternal book-keeper who has tallied up Marley’s good deeds and his sins, with the latter taking up the lion’s share of the ledger. As he is assigned, as Dickens described them, “the chains he forged in life,” Marley realizes that each condemned soul experiences his or her own personal Hell, where a manifestation of one’s particular sins serve as the tools of eternal torture. Marley’s punishment for his heartless greed and miserliness arrive in the traditional form of literal chains, bearing heavy cash boxes and other tools of his ruthless pursuit of wealth as a money-lender. With assistance from a damnation-borne, yet playfully charming sprite called Bogle, he is offered a single chance for escape from his fate; to redeem his partner, Ebenezer Scrooge, whose avarice and cruelty exceeded even Marley’s. (In a cheeky aside, Marley refers to Scrooge as the only man in the world worse than himself.) At first he is reluctant, but a shot at a reprieve is too tempting to resist, so Marley sets out, with Bogle in tow, on what seems an impossible mission. From here, the story takes on a sort of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern-esque quality, with familiar scenes and experiences seen through Marley’s eyes. His backstory is provided, and we discover that his childhood was as traumatic and depressing as Scrooge’s, with the two first meeting as teenage employees of Mr. Fezziwig, whom they eventually betray and drive out of business, taking over the firm for themselves. As the show progresses, we realize that Marley was actually all three of the Spirits of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet-To-Come, taking on different forms, but all the while witnessing Scrooge’s life choices and literally watching him turn into the “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner” of A Christmas Carol. Throughout the long night’s journeys, Marley softens on Scrooge, whom he actually despised in real life, and gradually replaces hatred with pity. To avoid a significant spoiler, I will simply say that Marley’s animus was well-placed, as we learn in his death scene, which makes his journey toward compassion all the more effective.

The script makes ample use of Dickens’ dialogue, and tosses in a few subtle references that die-hard fans of the original will enjoy. (“Easter eggs” in a story of Christmas, if you will.) Here I will give away one plot point that is not only clever, but completely changes the context of one of Scrooge’s lines in A Christmas Carol. Another apprentice at Fezziwig’s, Dick Wilkins, is seen cruelly bullying Marley, and it is Scrooge who comes to his defense, eventually leading to Wilkins’ fall into disgrace and penury. While taking Marley’s part in matters, Scrooge explains that he, too, has been bullied by Wilkins, and suggests that the two of them can bring an end to his cruelty as well as his situation. Devotees of the original will recall Scrooge seeing his tormentor in the Christmas Past flashback, and shouting ““Dick Wilkins, to be sure! Bless me, yes. There he is. He was very much attached to me, was Dick. Poor Dick! Dear, dear!” (As he was yet to have been reformed, Scrooge’s seemingly affectionate comment takes on a sinister tone when Wilkins’ true nature is revealed in this version.)

The rest of the show follows along fairly closely to the events of the original, with Marley growing more human as he watches Scrooge grow into the ogre he knew in life. It’s certainly no secret that Scrooge eventually repents and changes his ways, so we can assume that Marley manages to escape his torment.

As for the performances, there isn’t a weak link (pun once again intended) in the show. Kevin Bush, well-known to Columbia audiences, steps outside his usual wheelhouse of lovable and/or sympathetic characters to portray Marley as an absolute scoundrel and hard-edged “bad guy,” retaining a definite gruffness even as his humanity blossoms. Having always been impressed with Bush’s talent, my respect and admiration for his versatility cannot be understated. This is a role unlike any I have ever seen him tackle, and he succeeds as only a true master of his craft can. (He’s also a very nice guy in real life, which made it even more darkly delightful to watch him channel a hateful old bastard like Marley.)

All the other characters are played by three actors who match Bush’s skill and stage presence. Krista Forster’s Bogle manages to be otherworldly, cute, menacing, and fun simultaneously. Her physicality and use of the playing space often suggested the movements of a spider, yet her vocal and facial expressions maintained an undercurrent of saucy friendliness. Bogle is sassy, playful, and hilarious at times, yet always clearly in command of the situation, as well as Marley’s trip through his memories. Forster approaches it subtly, but leaves no doubt that Bogle is in charge and fully at ease, which provides a nice contrast to Marley’s initially stern (but eventually pointless) resistance to his task. Richard Edward III delivers an appropriately nasty and duplicitous Scrooge who is somehow even more tyrannical than Dickens’ character, yet never crosses over the line to caricature. While definitely making the character his own, Edward embodies his role with several Spirits of Scrooge Past (that was the third one, so I promise, no more puns.) Hints of George C. Scott’s interpretation are there, as well as a dash of Albert Finney’s and a moment or two of Kelsey Grammer’s, all connected by the fresh work of Edwards, who obviously did his research and then added his own vision. Jeff Driggers’ Bob Cratchit is as endearing as one would expect, but Driggers somehow makes him more three-dimensional than the too-kindly-to-be-true Cratchit often seen in A Christmas Carol. This Cratchit comes across as more of a decent fellow who has accepted the fact that he must take whatever his employer dishes out, as opposed to a simpering innocent. One of the things that has always perplexed me about Cratchit is his loyalty to Scrooge. Even in 1840s London, demeaning, low-paying jobs were not impossible to find, so why did Cratchit work for the worst employer in the city? Driggers artfully justifies this by adding a slight resignation to his fate, leaving the audience with the impression that while he could likely do better, it just isn’t worth the risk of missing even a few day’s pay, and he has decided to just make the best of his lot. Without giving away which plays whom, which would ruin the fun, I must emphasize that Forster, Edward, and Driggers all bring the same artistry to each of their additional roles.

On the technical side, Curtis Smoak’s lighting dovetails perfectly with Sam Hetler’s set, which is somewhat minimalist, but definitely evocative of the early Victorian era. As we follow Marley and Bogle, we visit a myriad of locales, which Smoak and Hetler manage to believably create. Costume Designer Jean Lomasto has, as usual, done outstanding work in dressing her actors in period style while maintaining the script’s eccentric nature, and Christine Hellman’s Hair Design deftly supports all of the above. This is a production crew that has obviously communicated well and brought the same sensibilities to each of their creations.

Director Patrick Michael Kelly has cast his show well, assembled a highly-skilled production team, and paced the show briskly, yet allows the actors to take the time they require in the moments where the audience needs to ponder and process what’s happening onstage. The smoothness of the production’s flow, and the undercurrent of suspense in what is, even in forced perspective, a well-known story are testimonials to Kelly’s vision and commitment to treating Jacob Marley’s Christmas Carol as the fresh, new(ish) piece that it is.

There are quite a few dark moments, even more so than in the original story, so this may not be the show for pre-teens who still enjoy Frosty and Rudolph, but should delight both Dickens aficionados and those encountering Marley, Scrooge, and the Spirits for the first time. Tickets are sure to sell quickly, so don’t delay in making your reservations for this splendid addition to the holiday canon. (And yes, there’s always wine and popcorn.)

Frank Thompson is proud to serve as Theatre Editor for JASPER, and can be reached at FLT31230@Yahoo.com