Workshop Theatre opened its 56th Season with Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie on Friday, September 15th at Cottingham Theatre at Columbia College. As this 78-year-old play is frequently included in high school literature curricula and regularly produced at community and professional theatres around the country, it is likely that many audience members have already had an experience with this play. It continues to relevantly examine escapism, unfulfilled desire, and familial responsibility in an old American South that is in conflict with modernity and advancement. Friday’s audience seemed to enjoy the production, leaning into the intended comedy of scripted moments, while also finding levity in moments that seemed absurd to contemporary audiences. For example: one of the biggest laughs came when a character decided to put a newspaper on top of a rug in order to “catch the drippings” of a candelabra that was being used to combat a blackout. The audience seemed to scream with their laughter: “Somebody call the Fire Marshal! This guy is nuts!”

A quick recap of the story: The Wingfields live in St. Louis, Missouri. The patriarch has long since abandoned the family, leaving them to fend for themselves. The matriarch, Amanda Wingfield, is an overbearing mother hellbent on refining her modern children and pushing them towards the life she wishes for them. Tom, her son (and the narrator of the play), is the main bread-winner of the family – working a very unsatisfying job at a shoe factory. Amanda is constantly badgering him about pretty much everything. Laura, the daughter, is an incredibly timid young woman who spends most of her time indoors with her phonograph and her animal figurines made of glass (cue title of the play). Amanda obsesses about Laura’s future, and after learning that her daughter’s anxiety has kept her from her typing classes – she insists on Tom finding a gentleman caller for his sister. He says he will, and indeed this former high-school hero, Jim O’Connor, comes to the house for dinner. Go see this production if you are not aware of what happens next.

In the first scene of the play, Tom Wingfield, played by Lamont Gleaton, steps onto his “safe place” – the fire escape outside of his home. Here, he tells the audience that what follows is a “memory play,” and that “nothing is real.” Thus, Williams has explicitly told the audience to expect the unexpected, while also freeing a director and production team to dream outside the constraints of slice-of-life realism and engage in the magic, idealism, romanticism and, sometimes, regret that memory can conjure. Workshop’s production, under the direction of Bakari Lebby, intentionally exercised creative freedom with their production rendering a thoughtful dive into the memory-world of the play that truly made this a 21st Century production - with mixed results.

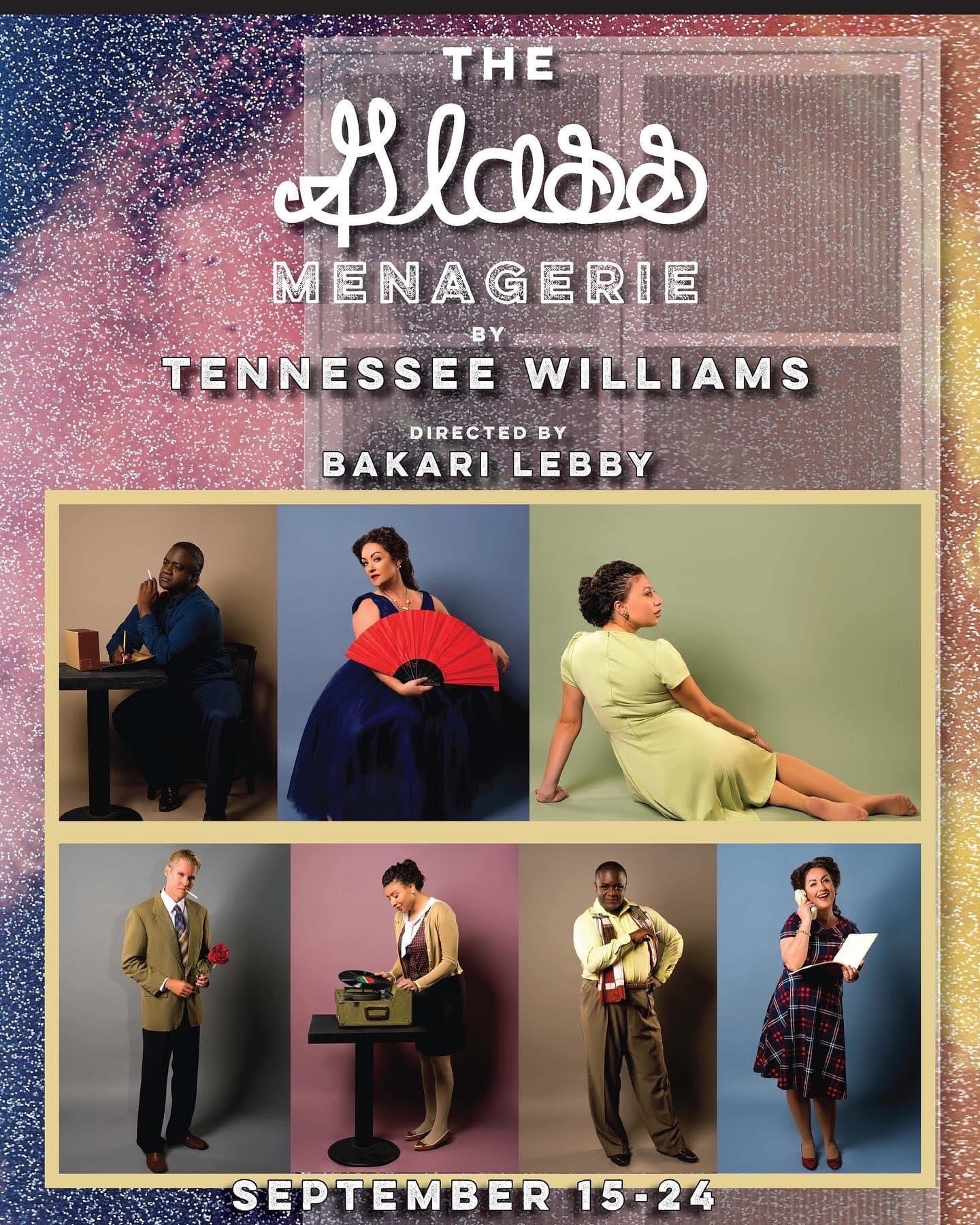

Workshop’s The Glass Menagerie is performed by an ensemble comprised of Columbia-based actors Lamont Gleaton (Tom Wingfield), Katie Mixon (Amanda Wingfield), Carly Siegel (Laura Wingfield), and Marshall Spann (Jim O’Connor). Contemporary productions of Williams and Arthur Miller plays are being cast more frequently with Actors of Color in the past 20 years here in America – offsetting the decades long practice of casting only white actors to portray the families that these playwrights created. The multiracial casting of Workshop’s Menagerie invites the audience to engage in a different kind of discomfort when witnessing Amanda Wingfield’s talon-tight grip on the old Southern way of life. When insisting she clean the table after a meal in Scene II, Amanda uses a racial epithet to describe her domestic services to the family – something that creates a unique tension on stage and in the audience as a white mother says this to her non-white children. The casting also begs more questioning of Amanda’s southern-fried prejudices within the context of her relationship to her now-absent husband. These questions provide good fodder for post-show conversation, but do not overshadow the author’s original intent during the performance – which focuses more on universal and poetic themes.

As Tom Wingfield, Lamont Gleaton was taxed with a large order to play an iconic character from the American canon. Having wowed audiences this time last year with his portrayal of Lola in Workshop’s Kinky Boots, this seems to be Gleaton’s first foray into non-musical theatre. He shines in scenes with other actors – letting his cool-heeled naturalism serve the play throughout. He particularly brought control to a scene where he returns home drunk from “going to the movies” – realistically exhibiting a man on a bender who is returning home to live a lie. Gleaton does seem to struggle with inviting the audience into the poetic monologues that connect the scenes all evening. Gleaton might gain more command as the production continues if he realizes that this story is Tom’s to tell.

Katie Mixon in the role of Amanda Wingfield was an audience favorite – she confidently commanded the stage as her character created most of the conflict in the play. Her portrayal was theatrical, outrageously comedic – and the audience rewarded it with laughter. However, this choice makes it seem that Amanda is not only in a different world in her head – it feels as if she is in a different play. Gone is the brutality and seething criticism that the character garners on the page, leaving the stakes low for Tom’s need for exodus and freedom, and completely eradicating the possible indications that Amanda’s narcissistic abuse exacerbates her daughter’s severe insecurity and anxiety. Still, when Mixon took her final bow – she was met with audience members who were inclined to stand to show their appreciation.

As Laura Wingfield, Carly Siegel was one of the strongest performers in the production. Siegel emphasizes the affliction of Laura’s anxiety disorder – a condition that, as we understand it today, can be a crippling disability. Though the character is traditionally portrayed with a limp or costumed to wear a leg-brace, this Laura does not. In 2023, we can totally acquiesce to the concept that this character’s timidness and fragility (a trait she sees in her glass figurines) is a product of her own anxiety which is made more severe through her mother’s scrutiny. Seigel beautifully executed the moment in the play when her “gentleman caller” accidentally causes the destruction of one of her beloved glass animals. She grows in the moment right in front of the audience – controlling her response and avoiding a sure panic attack.

Marshall Spann was a solid choice for the prized gentleman caller, Jim O’Connor, who finally enters the play in Act II. His charming portrayal of the character makes him a magnetic interest for Laura, while also welcoming allure from Amanda (and possibly Tom?). The scene in Act II in which Spann and Siegel are left alone on stage is very rewarding, with both actors creating a welcome tension between the possibilities of the future and their ultimate hopelessness.

Director Bakari Lebby and the design team present a very thoughtful concept of this memory play – accepting Williams’ scripted invitation to be inventive in creating the world on stage. A painted portrait of the absent father changes over the course of the play, with each following iteration becoming more and more abstract. The Wingfield home is a foundational structure that is faced with reflective material – making the set a literal glass enclosure from which the characters cannot escape. The sound design proffers a delightful mix of period-appropriate jazz that is peppered with contemporary music – drawing modern connections to the story and giving the audience permission to see how moments in the story could feel like “here and now.” Most notably, the media used in the show is instrumental in this production’s presentation of memory. Film clips that were filmed and edited specifically for this production were featured throughout the performance, giving the audience glimpses into the minds of these characters. These inventive and well-produced clips were shown on two TV’s nestled in the on-stage structure.

Ultimately these production design elements put a unique stamp on Workshop’s production of The Glass Menagerie. One can feel that these elements were intended for a larger presentation. Perhaps more specific lighting and projection mapping on the set could have elevated these elements to a more effective level for the audience. In the end, this production seems like a laboratory or workshop for a future production. Whether it was lack of resources or technical capabilities, this production suffers from a grander vision not being realized. This production should be seen and supported, because there is quite a bit of thought and inventiveness that went into it. The stylized concepts, though they could have been pushed much farther, do present Columbia with a new realization of this classic work. Tennessee Williams continues to prove that he was a skilled auditor of the human condition, and we can still see ourselves in these characters. The Glass Menagerie runs through September 24th at Cottingham Theatre at Columbia College, and you may book tickets at workshoptheatreofsc.com.