“Composure brings to light major issues that, after one-hundred and nineteen years, are still prevalent today. Fact versus interpretation of fact, truth versus bias, opinion-based reporting, righteous versus self-righteous, and the checks and balances between the press and the government…” - Jason Stokes, Playwright

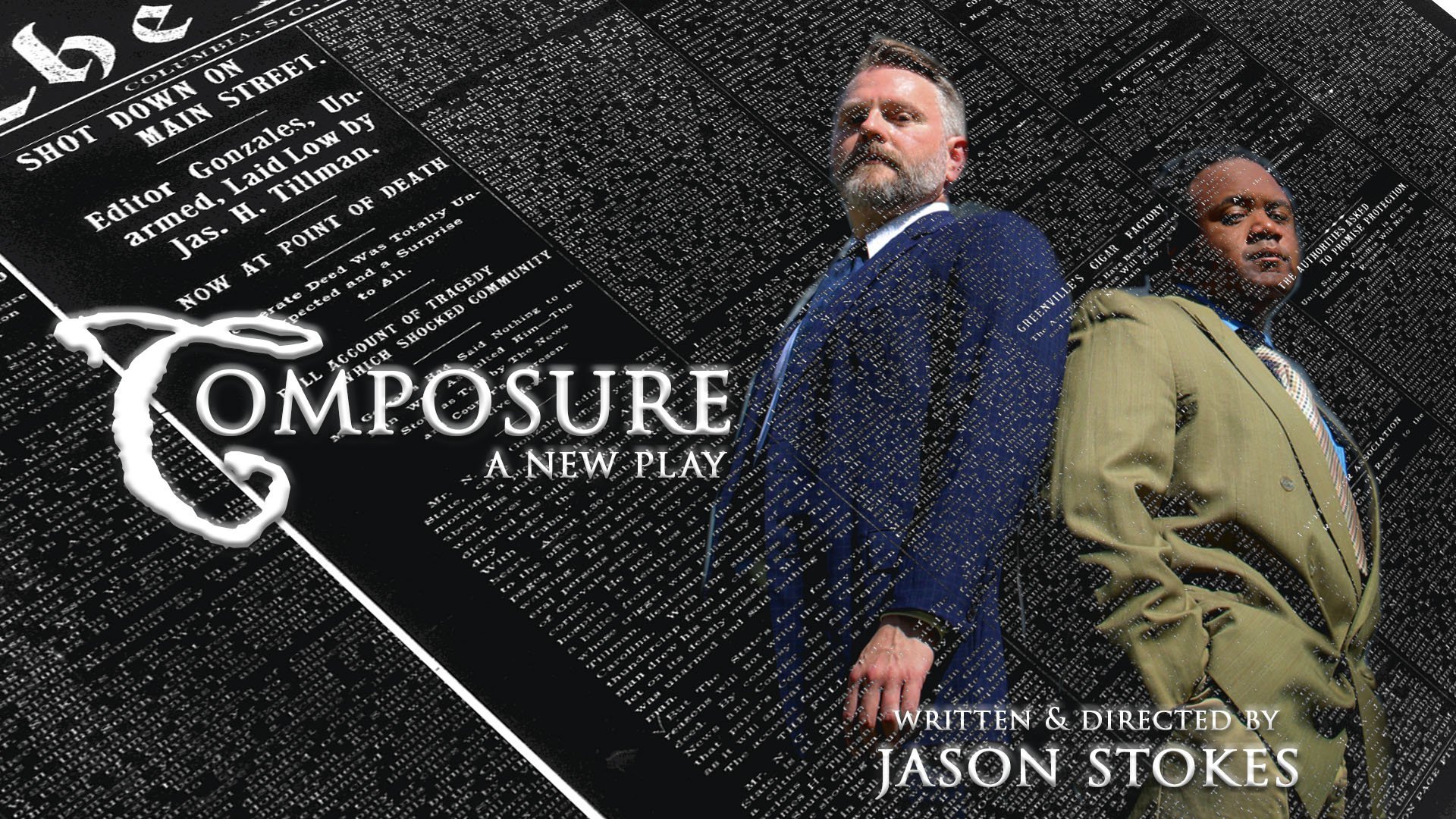

Pictured Clint Poston as James Tillman (left) and Jon Whit McClinton as N. G. Gonzales (right)

It’s been a long time coming for Jason Stokes, writer and director of the play Composure, which premiered Thursday night at Trustus Theatre. The inkling of the idea for presenting this story was born almost 20 years ago when Stokes first learned about this particularly sordid excerpt from South Carolina history that, in 1903, finds a white supremacist lieutenant governor, James Tillman, murdering in broad daylight N.G. Gonzales, journalist and co-founder of The State Newspaper, then walking away a free man. Stokes first developed the story as a screenplay before transforming it for the stage. It was scheduled to be premiered pre-Covid in cooperation with Chad Henderson, former artistic director of Trustus, along with Charlie Finesilver’s original production of House Calls, which premieres August 18th.

A larger story to be told than the one incident of the murder, Stokes does an impressive job of integrating the lead-up and aftermath of the shooting and trial into two acts. In fact, the structure of the play is highly sophisticated as the events and dialogue jump logically across place and time in order to explain not just most efficiently and dramatically the events, but the contributing causes of the events that took place.

The cast is, for the most part, stellar, with some of the finest actors Columbia has to offer on the stage in support of their colleague. It was a treat to see such accomplished actors as Hunter Boyle in the commanding role of Pitchfork Ben Tillman, Stan Gardner as attorney Patrick Nelson, G. Scott Wild as attorney William Thurmond, Kevin Bush as journalist J.A. Hoyt, and Terrance Henderson as Ambrose Gonzales, brother to murder victim N.G. Gonzales. Libby Campbell Turner displayed remarkable theatrical chops in her multiple cross-gendered roles as C.J. Terrel and additional characters, often changing characters on a dime just by adjusting the fit of her tie and her own composure. Her facial features and posture reminded the audience that she is a cast of characters unto herself. And Katie Leitner, as the long-suffering wife of the murderer, displayed a grace and elegance even when called upon to deliver the rare mellow-dramatic line. It was great, too, seeing Nate Herring back on the Trustus stage as George Lagare.

We were surprised, however, by some of the casting decisions.

With powerhouse artists like Bush, Wild, and Gardner on board, why were some of the most demanding roles assigned to some of the weaker actors on the team? As James Tillman, Clint Poston, though a fine supporting actor, was saddled with an incredibly challenging role, a role that seems made for the likes of G. Scott Wild who could so easily slide into the character of the blustery and entitled white Southern fascist Tillman must have been. Poston doesn’t seem to have a handle on how deluded and despicable Tillman was, sometimes coming off as somewhat sympathetic and misunderstood.

And while Brandon Martin at times rises to the level of contemptibility of future SC Governor and Senator Coleman Blease, a man who embraced white supremacy and lynching and violently opposed miscegenation, his physical appearance, posture, and contemporary hairstyle, as well as his time spent on stage when not speaking, make it difficult to believe him as the robust character of Cole Blease. Stan Gardner, on the other hand, would have soared in this role. (Since writing this, we have learned that Mr. Martin joined the cast at a late date to take the place of Stann Gwynn, an artist inordinately well suited to take on the role of Cole Blease. Jasper wishes the best both to Mr. Martin as he acclimates to the role and to Mr. Gwynn as he fully recovers from his medical procedure.)

But the most poorly cast actor, in a slate of otherwise excellent theatrical artists, was Jon Whit McClinton in the critical role of N.G. Gonzales. While McClinton was able to manage the side-role of judge most of the time, though he did break character and snicker at his own mistake at one point, he was out of his element among the artists with whom he shared the stage. The particularly jarring reality is that McClinton played opposite Terrance Henderson as Ambrose Gonzales in the majority of his scenes. Henderson’s stage presence, professionalism, and experience would have delivered a far more serious, and certainly less giddy, character than McClinton was able to provide.

We’re not sure whether Stokes conceptualized the set or if this was the singular purview of veteran scenic designer Danny Harrington, whose work has been a gift to most if not all theatre stages in the Columbia area, but the set for Composure, though problematic for the actors in places (Damn those pipes!), is a work of art itself. A play as complex as Composure could have required a multitude of scene changes. But Harrington’s innovative design—and the flexibility of the actors—allows for one large multi-use set that presents as something quite beautiful from the audience.

With a cast this size costuming can be a financial challenge and for the most part costume designer Andie Nicks does a fine job and, in some cases—like Katie Leitner’s elegant black and white skirted pants ensemble—an exceptional job. If financially possible, more consistency of style would be appreciated, too, particularly when it comes to pleats and cuffs for the gentlemen’s pants, hats vs. no hats, and the standard three button coat of the turn of the 20th century. And a good fit, no matter what the wardrobe, is ideal. Similarly, standardized hairstyles for men invite no comparison whereas the juxtaposition of a contemporary style, like that of Mr. Martin’s, stands out and begs notice, disrupting the flow of the play.

While kicking off the sound and lights posed a problem on Friday night, which Stokes managed with grace and humor, the lighting design by Teddy Palmer was helpful in guiding the audience’s attention to a stage in which, at times, as many as three scenes moved from frozen to active in a matter of seconds. In the best of all possible worlds (and budgets!) more intense spotlights would have been available, but in this world, this lighting worked fine. Background sounds by Jason Stokes were appropriate and complementary, with music added in places to enhance the setting but not overwhelm it.

Overall, it was a delight to see the vision of local multi-talented theatre artist and writer Jason Stokes become a reality. This play and its production are important to this community and beyond for a number of reasons.

Kudos to interim artistic director Dewey Scott-Wiley for following through on this project, begun by Stokes and Henderson, which could have fallen by the wayside once Covid forced its delay. We see far too little new stage work from an abundance of literary artists in SC and Columbia in particular. But local theatre and literary artists will continue to produce new art if given the opportunity to see it come to fruition, as Composure has. South Carolina and South Carolina playwrights have fascinating—and sometimes barely believable—stories to share, such as this story and that of Dr Ian Gale in next week’s premiere of House Calls: The Strange Tale of Dr. Gale.

Sadly, we are not as far removed from the issues and behavior depicted in Composure as we would like to think—we’re simply better at subterfuge. As Stokes writes in his playbill notes, “Composure brings to light major issues that, after one-hundred and nineteen years, are still prevalent today. Fact versus interpretation of fact, truth versus bias, opinion-based reporting, righteous versus self-righteous, and the checks and balances between the press and the government. Both are vital to American existence, both must keep careful watch on the other; but when these powerful forces become more self-aggrandizing entities than protectors of the people they serve, the American existence is lost.”

The question now is What’s next for Composure? Without question, the play should live on, possibly with a shorter first act, possibly continuing the model of more actors performing multiple roles to condense the cast. Some degree of workshopping might be helpful, but not a lot. This project strikes us as a good candidate for festivals. It’s a fascinating story that despite the passage of more than a hundred years still resonates and begs the same questions today that it did in 1903.

Congratulations to the cast and crew of Composure, a new play written and directed by Jason Stokes.