A quick trip down memory lane with a gorgeous Southern night sky and the subtle buzzing of insects. A brief respite from the metaphorical weight a person carries with them. The beauty within Staci Swider’s work goes beyond the visual aesthetic; it encompasses the intentions of the artist, and the potential for powerful conversation with anyone who stops to admire her work.

Art has been in Swider’s DNA since she was little. Learning how to sew from her grandmother, who happened to work in a children’s clothing factory, she was surrounded by knitting, needlepoint, fabrics, and anything craft oriented. “Growing up in the late 60s and early 70s, that was the resurgence of it as a craft form people were engaging with,” says Swider. “I have started to see artists start to crochet and sew again in our community nowadays, but that was what life was like back then!” Swider then went to school for fabric design and got into the workforce designing home furnishings. What she learned in school and during her career did end up shaping a lot of her practices and principles in terms of creating original work, along with the words of her grandmother: “a prayer for every stitch.” Finding the act of weaving to be very meditative, Swider subconsciously reflects on every loop and stitch beyond what it is creating in the physical plane. “Sometimes it isn’t about the finished product,” said Swider. “The act of doing is the real work. It gives you something to quiet your mind.”

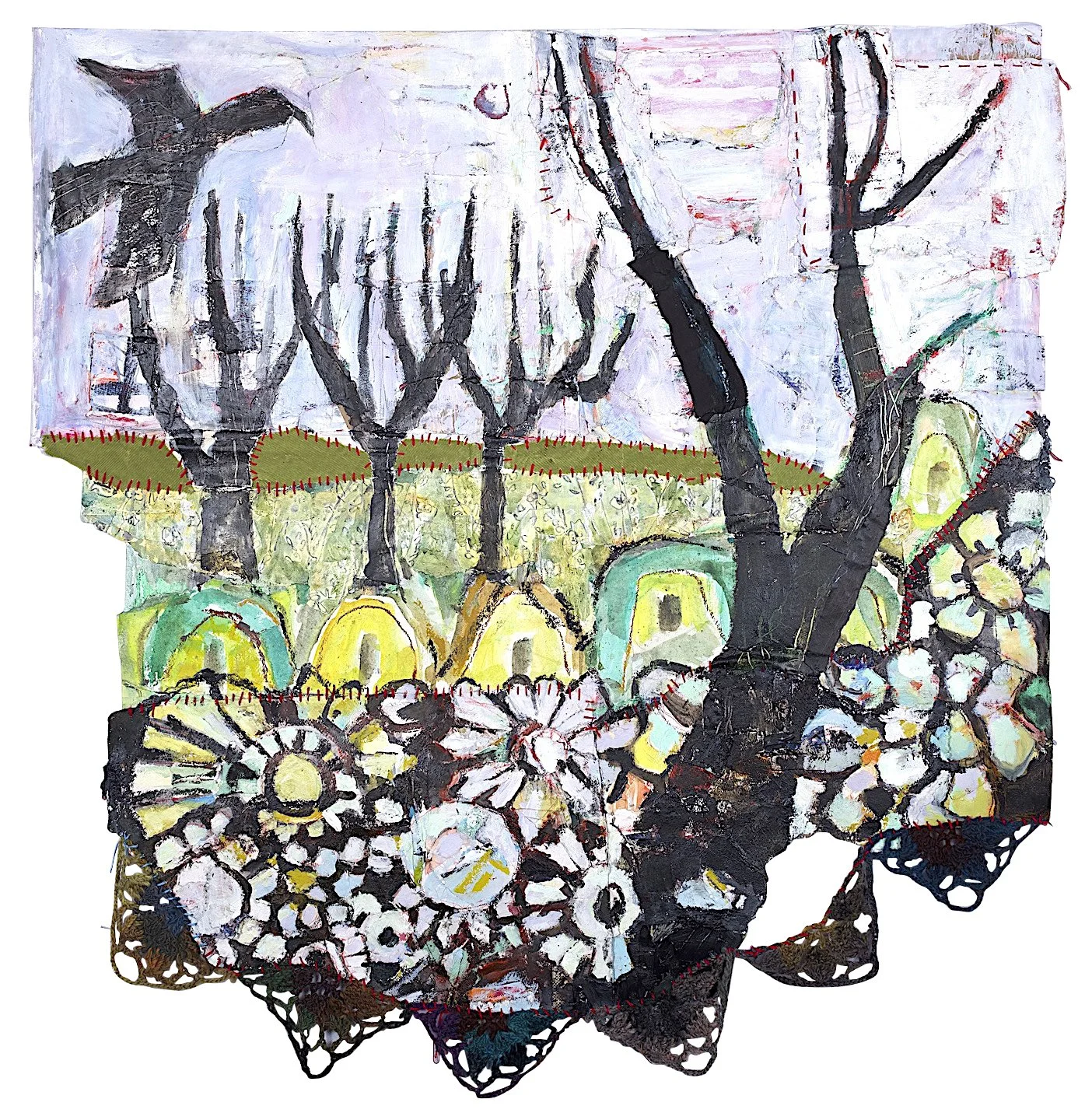

Swider’s background in textiles taught her to be attuned to finer details. She works with anything and everything fiber: yarn, thread, and fabric, then incorporates other materials like wire into the design to create both two-dimensional and three-dimensional works. These are not the only building blocks, however; Swider finds the exploration of contrast to be a major key in her work. “Contrast is not always just light and dark,” Swider says. “Sometimes, contrast in art focuses on the smooth versus rough, the busy and quiet, and finding the balance within a pair.” Weaving lends itself to be an optimal method of creating contrast, especially through Swider’s mastery of color work. She says, “On the surface, the color work appears as a quick snapshot that you take in, but when you come upon it and look closely it reveals itself further. You must look for the little things, like a piece of pink duct tape or cobalt silk that really sticks out in a section of one of my pieces.”

The visual building blocks of contrast, color, and the technical skills required of fiber arts all coalesce in works that capture the key theme of spirituality in Swider’s portfolio. Swider’s lens of the world is rooted in introspection and metaphorical conversation. "I express myself through a visual alphabet of symbols,” said Swider. “Not just runes or anything like that, but the actual images themselves in my work, and a lot of artists who tend to work metaphorically do something similar.” One notable example of the symbology is the arc shaped vessel in many pieces of Swider’s art. One may attribute it to being a literal boat at first glance, but the deeper meaning within the symbol goes beyond; rather, it is a vessel for everything one feels and does, a well of experience carried along a path in the work. It functions as a vessel for the other subject in the work as well as the viewer and are aptly referred to as “soul sleds.”

Conversation is integral to Swider as she aims to evoke a response in the viewer that they may or may not be able to articulate in words. Colors and images like a moody blue against a stark background may evoke a moody or contemplative feeling in the viewer. For Swider, “an image like a quiet night sky brings me to sitting in my backyard and listening to crickets.” As an empathic artist who feels a great sense of tension within her inner person, the imagery that Swider conveys in her work is a way for her to return to a specific moment and take a mental pause, allowing for a clear opportunity for introspection on how to proceed and respond to that tense feeling. The conversation with the viewer still continues through that introspection; after all, the viewer might be feeling the exact same way.

Having this exchange with the viewer completely remotely is exciting to Swider and feels as rewarding as if they were speaking face to face. “Whether or not a person likes the artwork I make or does not, they are still thinking about the work itself,” says Swider. “Whether they realize it or not, we are having a conversation about the work that way, which is a really beautiful thing to think about.”

The life that Swider has lived and the years of unique or shared experiences finds ways to express itself in her work. This experience lends itself to the key piece of advice Swider gives to any of her students or fellow artists who experience any sort of creative block: go back to the last place they felt artistically comfortable. Lessen the anxiety of creating something brand new and unfamiliar to themself by letting the creativity flow within familiar territory, like a flower arrangement for an artist who focuses on painting flowers. Set the mind at ease before attempting a new challenge, and the art block is much easier to overcome.

A life as an educator and full-time artist has paved the way for Swider to express her creativity in a multitude of ways beyond the visual arts. “At this point, my creativity leaks out into everything, like cooking and gardening,” said Swider. “I love to surround myself with beautiful things in my home, and to find beauty in anything and everything.” Living with intention and slowing down in an increasingly fast-paced world appeals greatly to Swider and has impacted her drive to continue interacting with things in her day-to-day life that makes her smile or feel uplifted.

The uplifting energy in her life carries through and feeds her creativity for the next piece Swider creates. The newest exciting opportunity to come Swider’s way is a grandiose exhibit at the Burroughs Chapin Museum in Myrtle Beach. Seizing the opportunity to work on her art and voice simultaneously, Tide Carriers, as Swider has named the project, focuses on three connected storylines that incorporate many of her new and old techniques along with exploratory discoveries she has made in other new projects, like her Unbuilt Rooms series.

"This maturity I have as a human and an artist, how does that get reflected in my work?” Swider asks. The optimal way to explore this was to create the three storylines: an expansion of the Unbuilt Rooms, the Soft Architecture of Rain, and the Songs of Becoming. The storylines follow a chronological reflection of Swider’s life, her evolution and where she finds herself now as a woman in her 60s in 2025. Starting with the Unbuilt Rooms, Swider explains these pieces as “the selves and dreams we carry within us but have not been realized.” These are not meant to be opportunities for the viewer to dwell on past choices that have been made, but rather, beacons of hope for them as they realize that their future still holds a great expanse of choices and dreams that can still be made and had.

The second piece of the narrative puzzle, the Soft Architecture of Rain, heavily incorporates the soul sled image, reiterating the weight of your hopes and dreams, longing, and baggage that they carry. This specific image joined Swider’s rotation in 2020 and is depicted both in two-dimensional and three-dimensional space. The incorporation of the vessels also enables Swider to express her attunement to her own empathy and operate as a moment of self-reflection both in the creation and viewing of the piece.

The odyssey concludes with the Songs of Becoming, where Swider maintains her agency as an older woman in a society that is so focused on the eternally youthful and naive. “Once upon a time, women of a certain age like me became the elders and leaders of a community,” says Swider. “They were the ones with the knowledge to pass on to the younger members in their community.” Swider poses the question of how she wants to be remembered through this section, and how she can embrace where she finds herself in the present day. The images in this section are filled with symbols of feminine power, such as extravagant headdresses that can even be worn when depicted in three dimensions. Swider’s art is 100% who she is now and continuously nurtures her identity; this dedicated exhibit brings all those feelings to the forefront for audiences to understand and perhaps empathize with.

Swider’s work must be seen to be fully understood. The intricate interplay of varied colors and materials creates a truly unique presence in the fiber arts realm. It is easy to get lost in the delicate rhythm of each piece, to drift into a long time behind you yet somehow still unfolding before you.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Jasper Magazine.